| Author: Guy Barrett | Title: Establishing a Family - (Chapter 10) |

| Date: 2002-12-28 18:39:48 | Uploaded by: webmaster |

|

Many a new fancier has wondered, when taking up the sport of pigeon racing, where he should buy his foundation stock, and whether they should be Old Birds, or Young. Should he obtain birds from one man only, or from several?

In a successful loft the birds are usually all of one ‘family’, that is, they are all descended from a few common ancestors and are thus all related in one way or another. Their owner has probably spent many years establishing this family, and has improved it over the years, by careful1y selecting his breeding pairs, and by rigorous testing of their progeny in the race basket. If the pedigrees of the birds were examined, it would probably be found that there are winners in each generation, and that the successful fancier has bred winners from winners, which were themselves bred out of winners.

The owner of a loft of pigeons such as these does not have to depend on one or two birds to win for him - he has many good pigeons capable of winning. He has concentrated the desirable qualities by generations of planned matings, and has purified the blood. There is one old saving, ‘Like begets like’, and another, “Like father, like son”, and both these phrases ring true when applied to a loft of birds which are a “family”.

It would be foolish for the novice to think that he could improve on the work of a really successful fancier until he has gained some experience. Therefore he should obtain birds from one man only. Were he to procure pigeons from several fanciers and pair them together, he would be destroying much of the good work done by each of those successful fanciers.

The novice should decide to purchase six or eight late-bred youngsters from his selected fancier, who should win year after year out of his turn, and preferably live locally or within easy visiting distance. No fancier who is racing can afford to part with his best racers or stock birds, except at a very high price. Also, no fancier will part with his best youngsters in April or May. He wants the first and second rounds of his very best birds for himself. Therefore, latebreds are the logical answer. In July and August it is possible to purchase youngsters from the pigeons, which have won during the Old Bird races, at no great cost, and these will make an ideal foundation stock. But (and this cannot be over-emphasised), they must all be from one successful fancier.

You may be sure that fanciers do not sell their good pigeons unless it is a clearance sale and, in these sales, the really good birds often fetch very high prices. Sometimes one sees an advertisement that reads, “Proved Stock Birds for sale - I have enough from them”, but if the birds offered were breeding winners, their owner could never “have enough from them”.

Tell the fancier that you intend to keep the latebred youngsters for stock. He will then (if he is genuine) take great pains to pick youngsters, which will have the best chance of breeding winners - those that are truly representative of the family. You cannot do better than leave the selection to him. Having procured your youngsters at about 24 to 26 days old, you should be able to take them home, confident that you have put one foot very firmly on the ladder, which leads to the top. Providing you do as you have promised, and keep the birds for stock, you will always be able to return for another pair at a later date and, if you manage them correctly, you will have just as good a chance of producing winners the following year as the established fancier from whom you have purchased the Young Birds.

The following season the birds should be paired at the beginning of March (on a sunny day), and two rounds of youngsters reared from each pair. Some useful advice on which bird to mate to which can often be obtained from their supplier. With luck, you should then have a dozen or so youngsters with which to fly the Young Bird programme. These should be carefully trained and raced to a distance of about a hundred miles, when the best six or eight should be stopped and allowed to rest and moult. You are then assured of having a small team of yearlings to race the next year.

Establishing a loft of pigeons is at least a four-year task, and the new fancier must be prepared to enter only a few of the races for the first season or two. If, after a year or so, it is found that one pair is breeding winners, it would seem to he common sense to keep that pair together, but otherwise the pairs can be changed each year amongst the original pigeons, and also these original birds can be paired to the younger birds bred by the new fancier himself.

This pairing of birds within the family is known as ‘line-breeding’. And if the relationships are really close, that is brother to sister, or father to daughter, it is called ‘in-breeding’. If you have a Labrador and you wish to breed another like it, you would not have it mated to an Alsatian. In the same way, there is always a better chance of producing winners from a winner, by pairing that winner to a bird from the same family.

It is true that many winners are produced out of a direct cross; that is when two unrelated birds are paired together. But the products of the cross themselves very rarely produce winners, unless they are mated to a relation on one side of the family. If this product of a cross is paired to an unrelated pigeon, that is out-crossed again, the qualities of the original pigeon have been lost and dispersed. After a direct cross, such as has been described above, it does not matter how close the relation is to which the progeny is paired.

We often read that such close ‘inbreeding’ should be avoided. Many people hold this opinion on religious or moral grounds. After all we humans are not allowed to marry very close relations. But inbreeding has the effect of purifying the blood. It concentrates the good qualities of the common ancestor, and also the bad qualities, where they are present. Therefore we may produce a super pigeon by pairing a champion to his daughter but, on the other hand, we may he unfortunate and breed an inferior specimen. But this does not matter with pigeons. We can get rid of the bird or, alternatively, it will be lost in a race. We should not, then, be afraid of arranging a close mating occasionally, although it should certainly not be indulged in for several successive generations, for this will result in loss of stamina.

Line-breeding, however, can be practised for many generations with distinct benefit to the stock. Such matings as grandsire to granddaughter (or great granddaughter), uncle to niece, half-brother to half-sister, come into this category. This method of arranging matings, so that the ‘blood’ of the important ancestor appears on both sides of the pedigree, is the one, which in my opinion is most likely to produce winners.

The mating of full brother to full sister does not appear to me to serve any useful purpose. It does not aim to reproduce either the father or the mother of these two birds, and the cock may have inherited entirely different qualities from his parents from those of his sister.

Consequently, in deciding which bird to pair to which, we should work on two main principles, namely: either pair the best to the best and hope to produce something better than either parent, or try to reproduce a champion pigeon already in existence by careful line or inbreeding.

Every fancier should make a study of that most interesting subject - the inheritance of colour and wing pattern. First, we must distinguish clearly between the different meanings of these terms. By colour, we mean either the Ash-Red or the ‘Blue-Black’ colour. By wing pattern, we mean either barred (as in the Blues and Mealies), light chequering, chequering, or dark chequering (as in the Dark chequers and Reds), Birds of the Ash-Red colour are the Mealies, Light Red chequers, Red chequers and the Reds, and their equivalents of the Blue-Black colour are the Blues, Light Blue chequers, Blue chequers and Dark chequers.

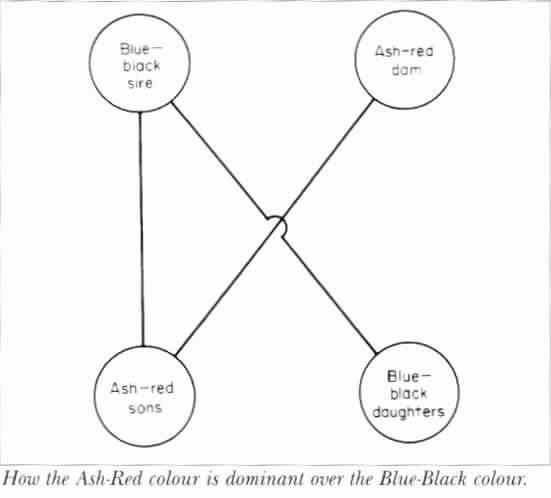

The important facts are these: when a pigeon inherits the Ash-Red colour from one parent and the Blue-Black colour from the other, the Ash-Red always prevails over the Blue-Black and the pigeon is of the Ash-Red colour. The Ash-Red is said to be the ‘dominant’ characteristic. The Blue-Black colour is suppressed and is said to be the ‘recessive’ characteristic.

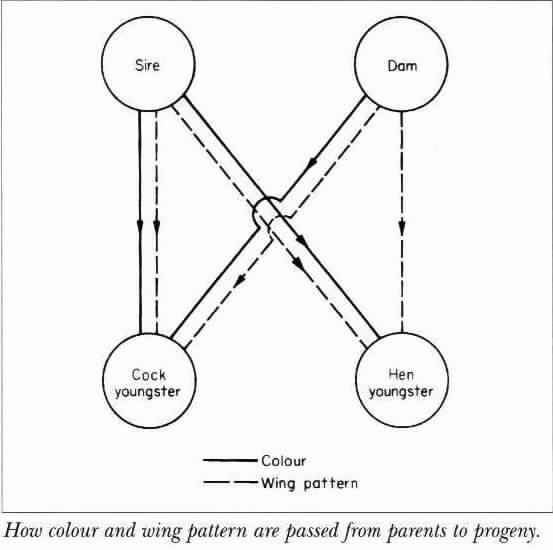

Hens only pass colour (Ash-Red or Blue-Black) to their sons. Cocks pass colour to both their sons and their daughters. Conversely, a cock inherits colour from both his sire and his dam. A hen only inherits colour from her sire.

Therefore when a Blue-Black cock is mated to an Ash-Red hen, the cock youngsters of the mating will inherit the Blue-Black colour from their sire and the Ash-Red colour from their dam. And since Ash-Red is dominant to Blue-Black, they will all be of the Ash-Red colour. So Red, Red chequer or Mealy hens cannot breed Blue or Blue chequer cocks. The hen youngsters of the mating will inherit the Blue-Black colour from their sire and no colour from their dam. Therefore they will all be of the Blue-Black colour.

The fact that cocks inherit colour from both sire and dam is the reason why some Red cocks have black flecks in the tail and wings, whereas hens - which only inherit colour from their sire - do not possess these flecks. Thus a cock which has inherited the Ash-Red colour from one parent, and the Blue-Black colour from the other, will be of the Ash-Red colour with black flecks. He will be able to pass on to his progeny either the Ash-Red or the Blue-Black colour. The hen is the colour, which she has inherited and that is the colour she passes to her sons.

The wing pattern is passed from both parents to both sons and daughters. Thus a Blue cock, paired to a Blue chequer hen, could produce Blue and Blue chequer cocks and Blue and Blue chequer hens.

The bird shows an inherited darker wing pattern rather than a lighter one, as the darker must necessarily mask the lighter pattern. A pigeon which has inherited the barred pattern from one parent, and the dark chequer pattern from the other, will obviously appear as a dark chequer, but it could pass on to its offspring either of these two patterns. If it were mated to a Blue, it would produce either dark chequers or Blues. Similarly Blues and Mealies must have received the barred pattern from both parents, and this is the only pattern, which they can pass to their progeny. In pieds, which is the name given to birds which have a number of white feathers, the white colour masks the colour ‘beneath’ and it is amazing how a gay pied (one with the majority of its feathers white) is produced occasionally from two birds which possess very few white feathers.

In this short explanation of how colour and wing pattern are passed from the parent birds to their offspring, the use of scientific terms has been deliberately avoided, and it is hoped that because the subject has been treated this way, it will be more readily understandable than might otherwise have been the case.

Perhaps the following further example will illustrate all the points raised. A dark chequer (Blue-Black) cock is mated to a Mealy (Ash-Red) hen. The cock was bred from a Dark chequer cock and a Blue hen. What colours can we expect the progeny of this mating to be? Firstly, we know that all the cocks will be of the Ash-Red colour and the hens of the Blue-Black. Therefore, the young cocks will be either Reds (the equivalent of the Dark chequer, but of the Ash-Red colour) or Mealies, and the hens will be either dark chequers or Blues.

On the continent, fanciers always seem to have many more stock pigeons, which are kept solely for breeding purposes than we do. This is because most of them only fly on the Widowhood System, and therefore cannot breed a second round of squeakers from their racers, as we can, flying on the Natural System. But the Widowhood System has much to recommend it. If the Continental fancier is unfortunate and has a very bad race, thereby losing many of his best racers, he can nearly always breed more like them, as he has the parents safely in the stock-loft. We often find, that by the time we realise we have bred a champion; we have lost its parents.

There is a lesson to be learned from this. We must always be on the lookout for a potential breeder of winners. And as soon as we have found this pigeon - be it cock or hen - it must be withdrawn immediately from the racing team, and reserved for stock. We must be prepared to forgo any success, which that pigeon might achieve in the races and build for the future.

Pigeons, which consistently turn out winners every year, are worth their weight in gold. And the sooner in their life, that their merit can be recognised, the more years will be available for it to be used. It is far better to stop a breeder of winners from racing in the prime of its life, and put it to stock, than to wait until it is too old to race. Even the best Old pigeon can be lost in an effort to extract one more winning performance from it and in addition the offspring it would have bred, had it remained in the loft for a number of years in well-earned retirement, are lost forever. This is one of the best ways of ensuring that, once we have reached the top, we stay there.

Providing they maintain their health and vitality, there is no reason why good stock pigeons should not continue to produce winners for many years. I have two old cocks (one 15 and the other 14), which are still breeding winners. The elder of the two is just beginning to show his age, but the other has all the energy of a two year old.

Just as cattle breeders try to improve the quality of their beef herds and the milk yield of their cows, so we must, by careful selection and well-thought-out matings, endeavour to improve the racing ability of our pigeons. As the years go by, if we are successful in our efforts, we shall find that we are losing fewer birds, and that we are breeding a greater percentage of good pigeons. Also, we shall discover that our birds are breeding true to type, and that certain pigeons appear in the pedigrees of nearly all of them. In fact, we have achieved what we set out to do, and have ‘established a family’.

Used with permisson. © RPRA.

|

| Coo time for a brew!...Where next? |

| Lets hear what you've got to say on this issue.... or any other infact! Post your comments in the Message Forum. |

| You've seen the light... bang a new idea!!... Tell the world, Write an article for Pigeonbasics.com, email into the webmaster at webmaster@pigeonbasics.com. |

|

|